The introduction of new surgical procedures is fraught with difficulty. Determining that a procedure is safe to perform while surgeons are still learning how to do it has obvious problems. Comparing a new procedure to existing treatments requires the surgery to be performed on a scale rarely available at early stages of development. The IDEAL framework helps greatly with this process.

When performing liver surgery, it is crucial that sufficient liver is left behind at the end of the operation to do the necessary job of the liver. This is particularly important in the first days and weeks following surgery. When disease demands that a large proportion of the liver is removed, manoeuvres can be performed before surgery to increase the size of the liver left behind. The disease is invariably cancer and the manoeuvres usually involves blocking the vein supplying the part of the liver to be removed, a procedure called portal vein embolisation. This causes the liver to think part of it has already been removed. The part which will stay behind after surgery increases in size, hopefully sufficient to do the job of the liver after surgery. This often works but does require a delay in definitive surgery and in some patients does not work sufficiently well.

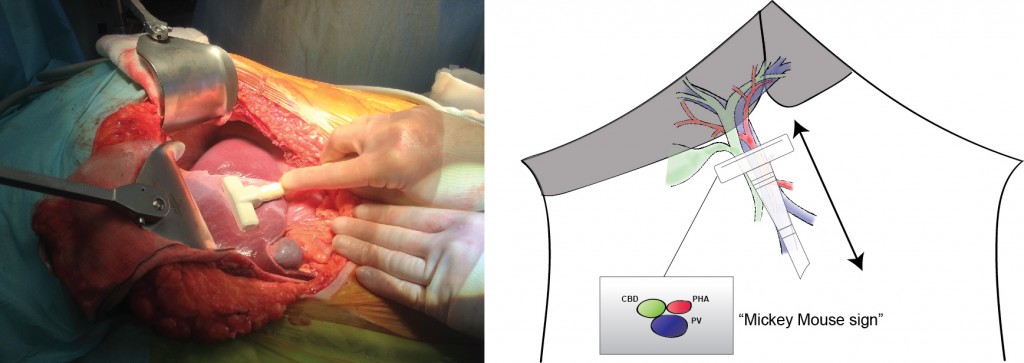

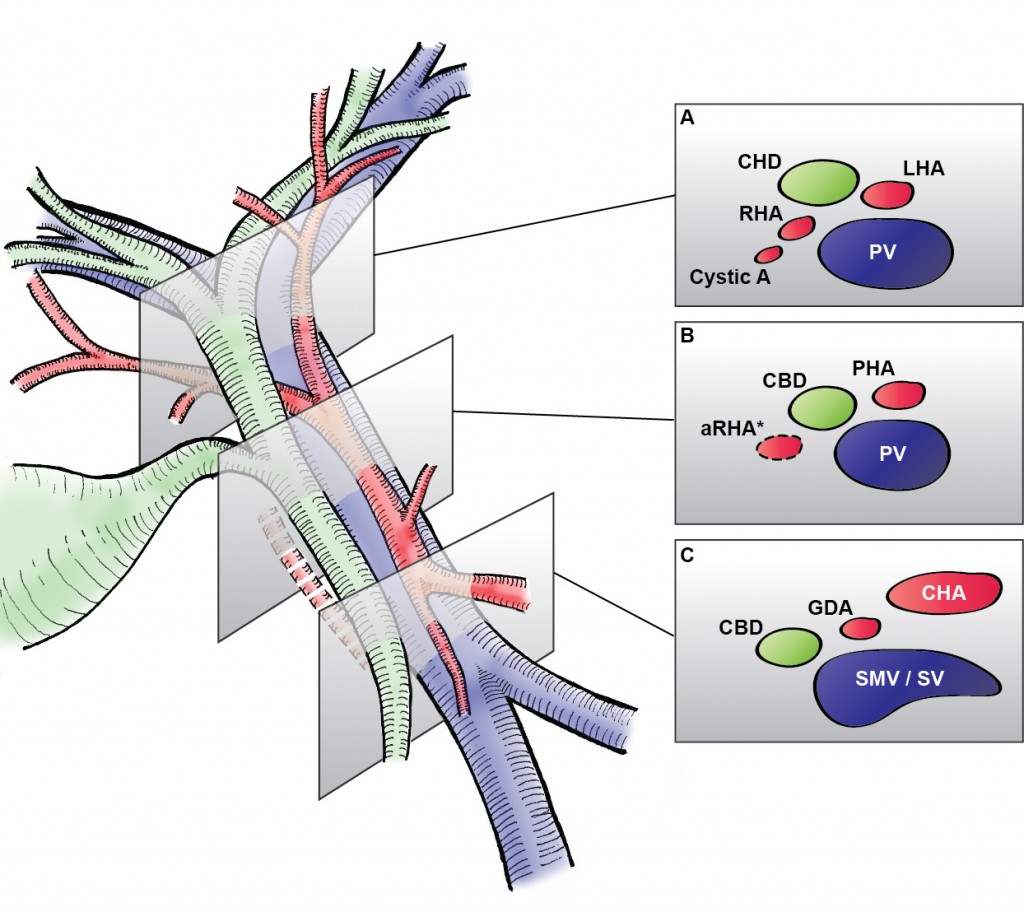

An alternative procedure has come to the fore recently. The ALPPS procedure (Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein Ligation for Staged Liver resection) combines this embolisation procedure with an operation to cut the liver along the line required to remove the diseased portion. But after making the cut, the operation is stopped and the patient woken up. Over the course of the following week the liver being left behind increases in size – quicker and more effectively say proponents of the ALPPS procedure. After a week, the patient is taken back to the operating room and the disease liver portion removed.

So should we start using the procedure to treat cancer which is widely spread in the liver?

The difficulty is knowing whether the new procedure is safe and effective. Early results suggest quite a high mortality associated with the procedure. But of course for patients with untreated cancer in the liver who do not have surgery, the mortality rate is high.

A study has been published which contains some positive data: ALPPS offers a better chance of complete resection in patients with primarily unresectable liver tumors compared with conventional-staged hepatectomies: results of a multicenter analysis.

However, it is still my feeling that the results of the procedure are not good and the traditional portal vein embolisation procedure seems to work well in our patients. Here is our letter with our concerns in response.

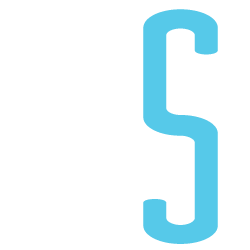

We read with interest the multicenter study by Schadde and colleagues in the April issue regarding the novel procedure of Associating Liver Partition and Portal vein Ligation for Staged Liver resection (ALPPS) [1]. Since the initial description 2 years ago [2] ALPPS has gained popularity as a surgical option for treating patients with advanced liver lesions not considered amenable to conventional two-stage or future liver remnant-enhancing procedures propagated by Rene Adam et al. [3] a decade ago. Indeed, the explosion of interest in ALPPS by surgeons and its adoption as a procedure of choice is concerning, given that the procedure appears to come with considerable cost to the patient, as shown in this study. The increased severe morbidity of 27 versus 15 % and the mortality of 15 versus 6 % may not achieve traditional measures of statistical significance in this study, but the effect size is concerning, and the direction of effect is consistent across outcome measures and studies. Is ALPPS in its current form safe enough for the widespread adoption that has occurred given increasingly effective nonsurgical approaches, including ablation, chemotherapy, selective internal radiation therapy [4], and growth factor/receptor inhibition?

As the authors rightly point out, the risk of selection bias is significant given the study design. It is unclear whether the logistic regression analysis adequately adjusts for the imbalance in baseline risk in favor of the ALPPS group: why, for instance, was operative risk (ASA grade) not controlled for in the multivariate analysis?

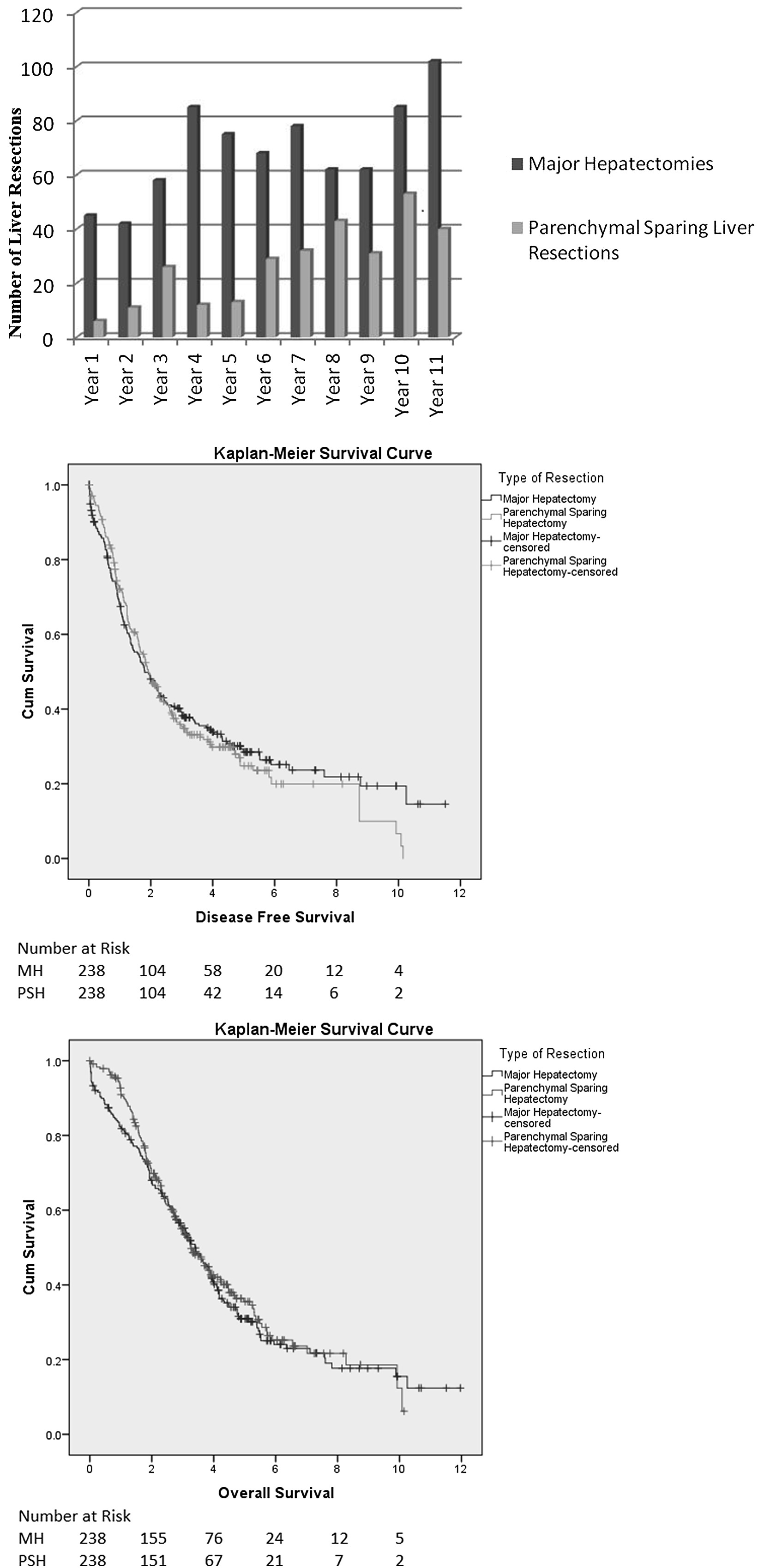

One of the potential benefits of a two-stage procedure is that it may disclose biologically unfavorable disease. By its very nature, ALPPS does not lend itself to such selection given the short time interval between the first and second stages. The authors appear to reject this argument, citing a similar overall recurrence rate seen in this study. We were puzzled with this position given that the study highlights an interesting observation: in the PVE/PVL group 11 % of patients had systemic progression prior to the second stage. Presumably this group of patients would not have benefitted from ALPPS.

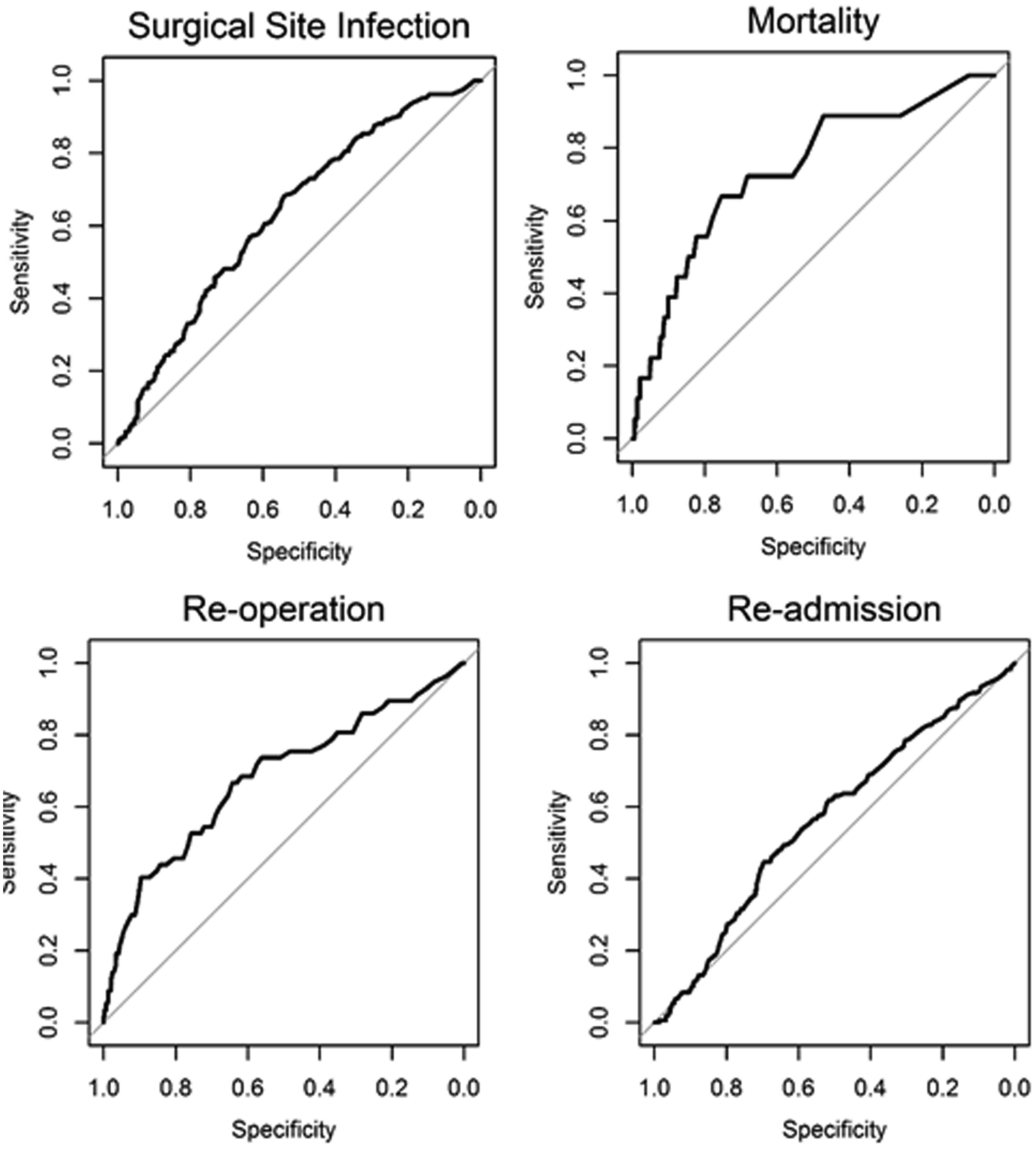

In our practice, patients who may be deemed by others to be ideal candidates for ALPPS are seldom not amenable to either a two-stage liver resection or a single-stage resection with prior volume-enhancing maneuvers. Indeed, it is difficult to understand why an ALPPS approach was used at all in some of the cases presented at recent international conferences. We wonder what proportion and kind of patients with advanced liver lesions would really benefit from the ALPPS approach. The international ALPPS registry will perhaps provide clearer evidence for the role of this challenging approach to liver resection.

1. Schadde E, Ardiles V, Slankamenac K et al (2014) ALPPS offers a better chance of complete resection in patients with primarily unresectable liver tumors compared with conventional-staged hepatectomies: results of a multicenter analysis. World J Surg 38:1510–1519. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2513-3

2. Schnitzbauer AA, Lang SA, Goessmann H et al (2012) Right portal vein ligation combined with in situ splitting induces rapid left lateral liver lobe hypertrophy enabling 2-staged extended right hepatic resection in small-for-size settings. Ann Surg 255:405–414

3. Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G et al (2004) Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg 240:644–657 discussion 657–658

4. Gulec SA, Pennington K, Wheeler J et al (2013) Yttrium-90 microsphere-selective internal radiation therapy with chemotherapy (chemo-SIRT) for colorectal cancer liver metastases: an in vivo double-arm-controlled phase II trial. Am J Clin Oncol 36:455–460

[gview file=”http://www.datasurg.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Rohatgi-et-al.-2014-ALPPS-Adverse-Outcomes-Demand-Clear-Justification.pdf”]