As Niels Bohr, the Danish physicist, put it, “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future”. Prognostic models are commonplace and seek to help patients and the surgical team estimate the risk of a specific event, for instance, the recurrence of disease or a complication of surgery. “Decision-support tools” aim to help patients make difficult choices, with the most useful providing personalized estimates to assist in balancing the trade-offs between risks and benefits. As we enter the world of precision medicine, these tools will become central to all our practice.

In the meantime, there are limitations. Overwhelming evidence shows that the quality of reporting of prediction model studies is poor. In some instances, the details of the actual model are considered commercially sensitive and are not published, making the assessment of the risk of bias and potential usefulness of the model difficult.

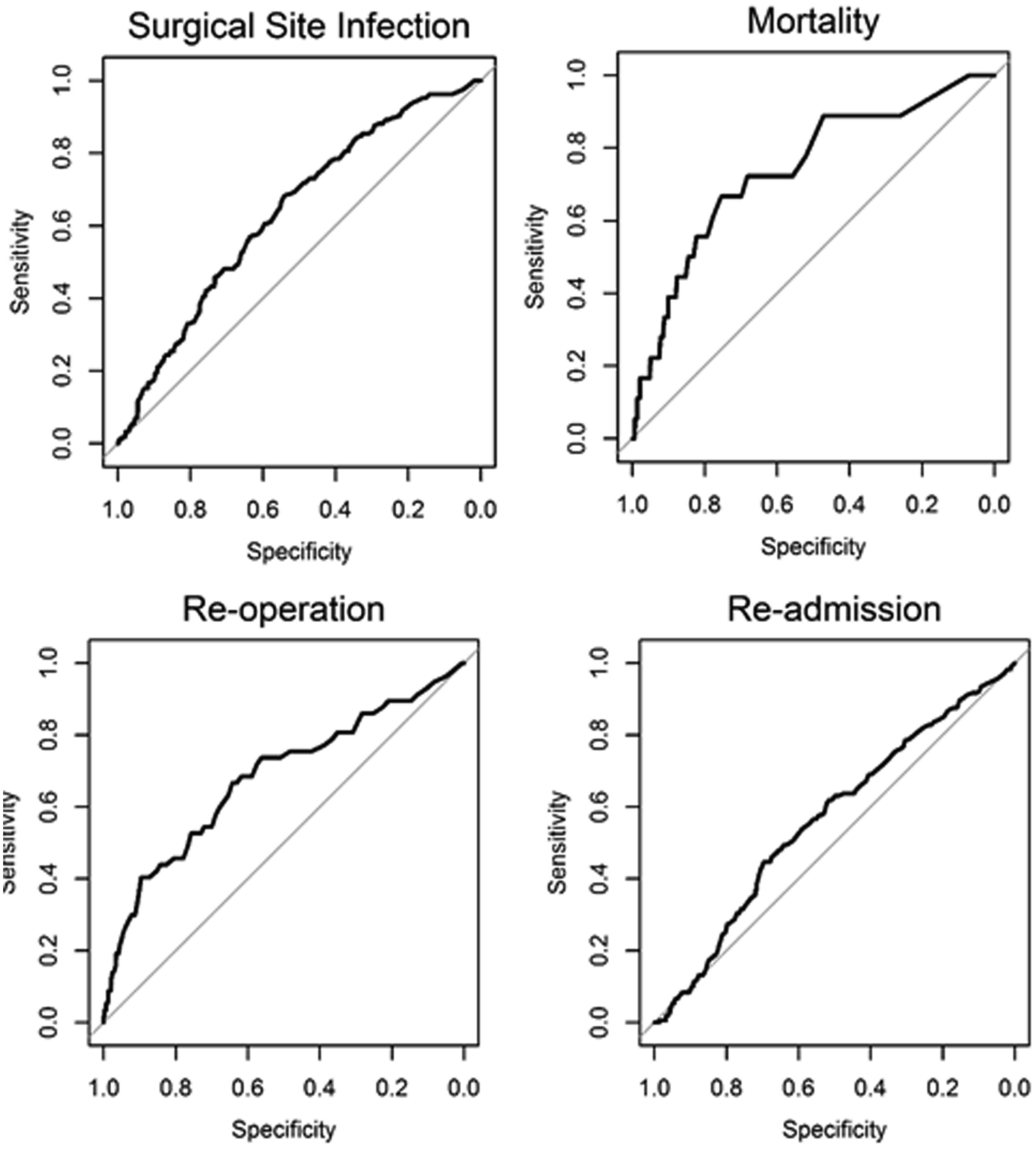

In this edition of HPB, Beal and colleagues aim to validate the American College of Surgeons National Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) Surgical Risk Calculator (SRC) using data from 854 gallbladder cancer and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients from the US Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. The authors conclude that the “estimates of risk were variable in terms of accuracy and generally calculator performance was poor”. The SRC underpredicted the occurrence of all examined end-points (death, readmission, reoperation and surgical site infection) and discrimination and calibration were particularly poor for readmission and surgical site infection. This is not the first report of predictive failures of the SRC. Possible explanations cited previously include small sample size, homogeneity of patients, and too few institutions in the validation set. That does not seem to the case in the current study.

The SRC is a general-purpose risk calculator and while it may be applicable across many surgical domains, it should be used with caution in extrahepatic biliary cancer. It is not clear why the calculator does not provide measures of uncertainty around estimates. This would greatly help patients interpret its output and would go a long way to addressing some of the broader concerns around accuracy.