I do a fair amount of peer-review for journals. My totally subjective impression – which I can’t back up with figures – is that fundamental errors in data analysis occur on a fairly frequent basis. Opaque descriptions of methods and no access to raw data often makes errors difficult to detect.

We’re performing a meta-analysis at the moment. This is a study in which two or more clinical trials of the same treatment are combined. This can be useful when there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of a treatment.

Relevent trials are rigorously searched for and the quality assessed. The results of good quality trials are then combined, usually with more weight being given to the more reliable trials. This weight reflects the number of patients in the trial and, for some measures, the variability in the results. This variation is important – trials with low variability are greatly influential in the final results of the meta-analysis.

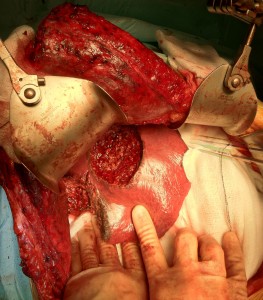

What are we doing the meta-analysis on? We often operate to remove a piece of liver due to cancer. Sometimes we have to clamp the blood supply to the liver to prevent bleeding. An obvious consequence to this is damage to the liver tissue.

It may be possible to protect the liver (and any organ) from these damaging effects by temporarily clamping the blood supply for a short time, then releasing the clamp and allowing blood to flow back in. The clamp is then replaced and the liver resection performed. This is called “ischemic preconditioning” and may work by stimulating liver cells to protect themselves. “Batten down the hatches boys, there’s a storm coming!”

Results of this technique are controversial – when used in patients some studies show it works, some show no benefit. So should we be using it in our day-to-day practice?

We searched for studies examining ischemic preconditioning and found quite a few.

One in particularly performed by surgeons in Hungary seemed to show that the technique worked very well (1).The variability in this study was low as well, so it seemed reliable. Actually the variability was very low – lower than all the other trials we found.

The graph shows 3 of the measures used to determine success of the preconditioning. The first two are enzymes released from damaged liver cells and the third, bilirubin, is processed by the liver. All the studies show some lowering of these measures signifying potential improvement with the treatment. But most trials show a lot of variation between different patients (the vertical lines).

Except a Hungarian study, which shows almost no variation.

Even compared with a study in which these tests were repeated between healthy individuals in the US (9), the variation was low. That seemed strange. Surely the day-to-day variation in your or my liver tests should be lower than those of a group of patients undergoing surgery?

It looks like a mistake.

It may be that the authors wrote that they used one measure of variation when they actually used another (standard error of the mean vs. standard deviation). This could be a simple mistake, the details are here.

But we don’t know. We wrote three times, but they didn’t get back to us. We asked the journal and they are looking into it.

1 Hahn O, Blázovics A, Váli L, et al. The effect of ischemic preconditioning on redox status during liver resections-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2011;104:647–53.

2 Clavien P-A, Selzner M, Rüdiger HA, et al. A Prospective Randomized Study in 100 Consecutive Patients Undergoing Major Liver Resection With Versus Without Ischemic Preconditioning. Annals of Surgery 2003;238:843–52.

3 Li S-Q, Liang L-J, Huang J-F, et al. Ischemic preconditioning protects liver from hepatectomy under hepatic inflow occlusion for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10:2580–4.

4 Choukèr A, Martignoni A, Schauer R, et al. Beneficial effects of ischemic preconditioning in patients undergoing hepatectomy: the role of neutrophils. Arch Surg 2005;140:129–36.

5 Petrowsky H, McCormack L, Trujillo M, et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial Comparing Intermittent Portal Triad Clamping Versus Ischemic Preconditioning With Continuous Clamping for Major Liver Resection. Annals of Surgery 2006;244:921–30.

6 Heizmann O, Loehe F, Volk A, et al. Ischemic preconditioning improves postoperative outcome after liver resections: a randomized controlled study. European journal of medical research 2008;13:79.

7 Arkadopoulos N, Kostopanagiotou G, Theodoraki K, et al. Ischemic Preconditioning Confers Antiapoptotic Protection During Major Hepatectomies Performed Under Combined Inflow and Outflow Exclusion of the Liver. A Randomized Clinical Trial. World J Surg 2009;33:1909–15.

8 Scatton O, Zalinski S, Jegou D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ischaemic preconditioning in major liver resection with intermittent Pringle manoeuvre. Br J Surg 2011;98:1236–43.

9 Lazo M, Selvin E, Clark JM. Brief communication: clinical implications of short-term variability in liver function test results. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:348–52.