This is our new analysis of an old topic.In Scotland, individual surgeon outcomes were published as far back as 2006. It wasn’t pursued in Scotland, but has been mandated for surgeons in England since 2013.

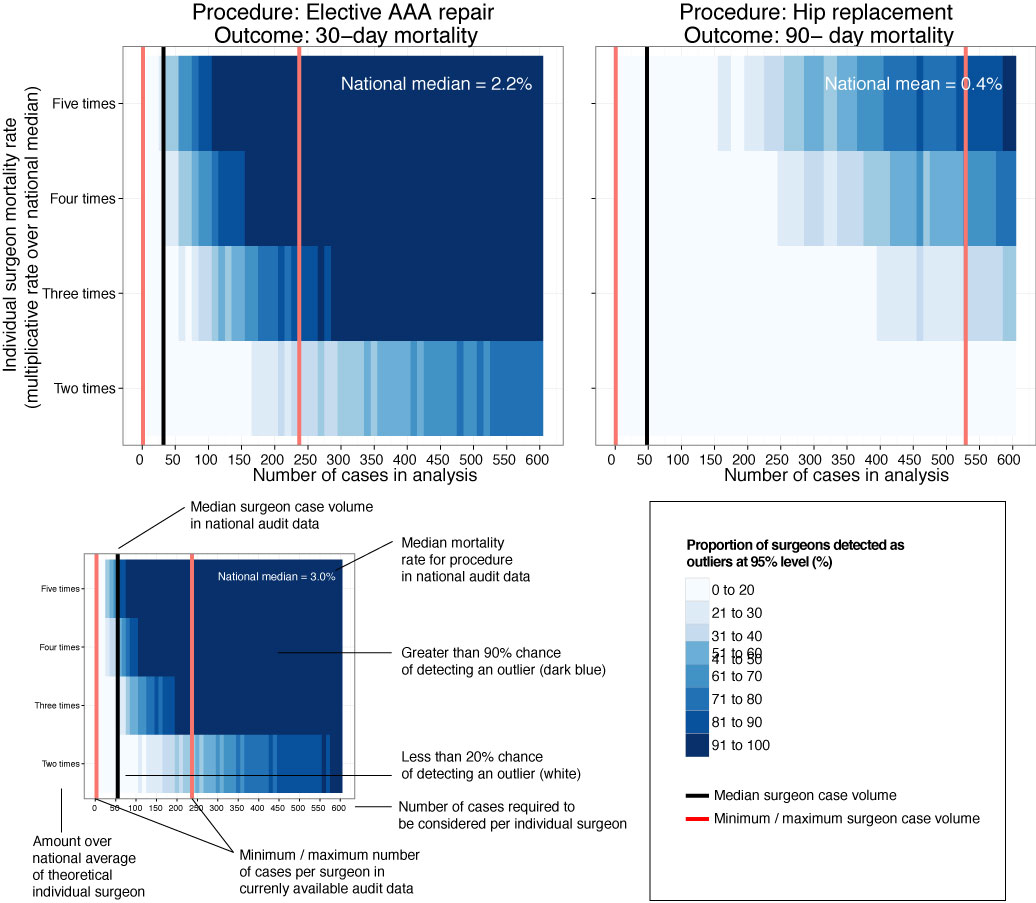

This new analysis took the current mortality data and sought to answer a simple question: how useful is this information in detecting differences in outcome at the individual surgeon level?

Well the answer, in short, is not very useful.

We looked at mortality after planned bowel and gullet cancer surgery, hip replacement, and thyroid, obesity and aneurysm surgery. Death rates are relatively low after planned surgery which is testament to hard working NHS teams up and down the country. This together with the fact that individual surgeons perform a relatively small proportion of all these procedures means that death rates are not a good way to detect under performance.

At the mortality rates reported for thyroid (0.08%) and obesity (0.07%) surgery, it is unlikely a surgeon would perform a sufficient number of procedures in his/her entire career to stand a good chance of detecting a mortality rate 5 times the national average.

Surgeon death rates are problematic in more fundamental ways. It is the 21st century and much of surgical care is delivered by teams of surgeons, other doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacists, dieticians etc. In liver transplantation it is common for one surgeon to choose the donor/recipient pair, for a second surgeon to do the transplant, and for a third surgeon to look after the patient after the operation. Does it make sense to look at the results of individuals? Why not of the team?

It is also important to ensure that analyses adequately account for the increased risk faced by some patients undergoing surgery. If my granny has had a heart attack and has a bad chest, I don’t want her to be deprived of much needed surgery because a surgeon is worried that her high risk might impact on the public perception of their competence. As Harry Burns the former Chief Medical Officer of Scotland said, those with the highest mortality rates may be the heroes of the health service, taking on patients with difficult disease that no one else will face.

We are only now beginning to understand the results of surgery using measures that are more meaningful to patients. These sometimes get called patient-centred outcome measures. Take a planned hip replacement, the aim of the operation is to remove pain and increase mobility. If after 3 months a patient still has significant pain and can’t get out for the groceries, the operation has not been a success. Thankfully death after planned hip replacement is relatively rare and in any case, might have little to do with the quality of the surgery.

Transparency in the results of surgery is paramount and publishing death rates may be a step towards this, even if they may in fact be falsely reassuring. We must use these data as part of a much wider initiative to capture the success and failures of surgery. Only by doing this will we improve the results of surgery and ensure every patient receives the highest quality of care.

Read the full article for free here.

Press coverage

Radio: LBC, Radio Forth

Print:

- New Scientist

- Scotsman

- Daily Mail

- Express

- the I

Online:

ONMEDICA, SHROPSHIRESTAR.COM, THE BOLTON NEWS, EXPRESSANDSTAR.COM, BELFAST TELEGRAPH, AOL UK, MEDICAL XPRESS, BT.COM, EXPRESS.CO.UK